PA Talks 003 | Ferda Kolatan – Hybridity in Architecture | at GAD Foundation

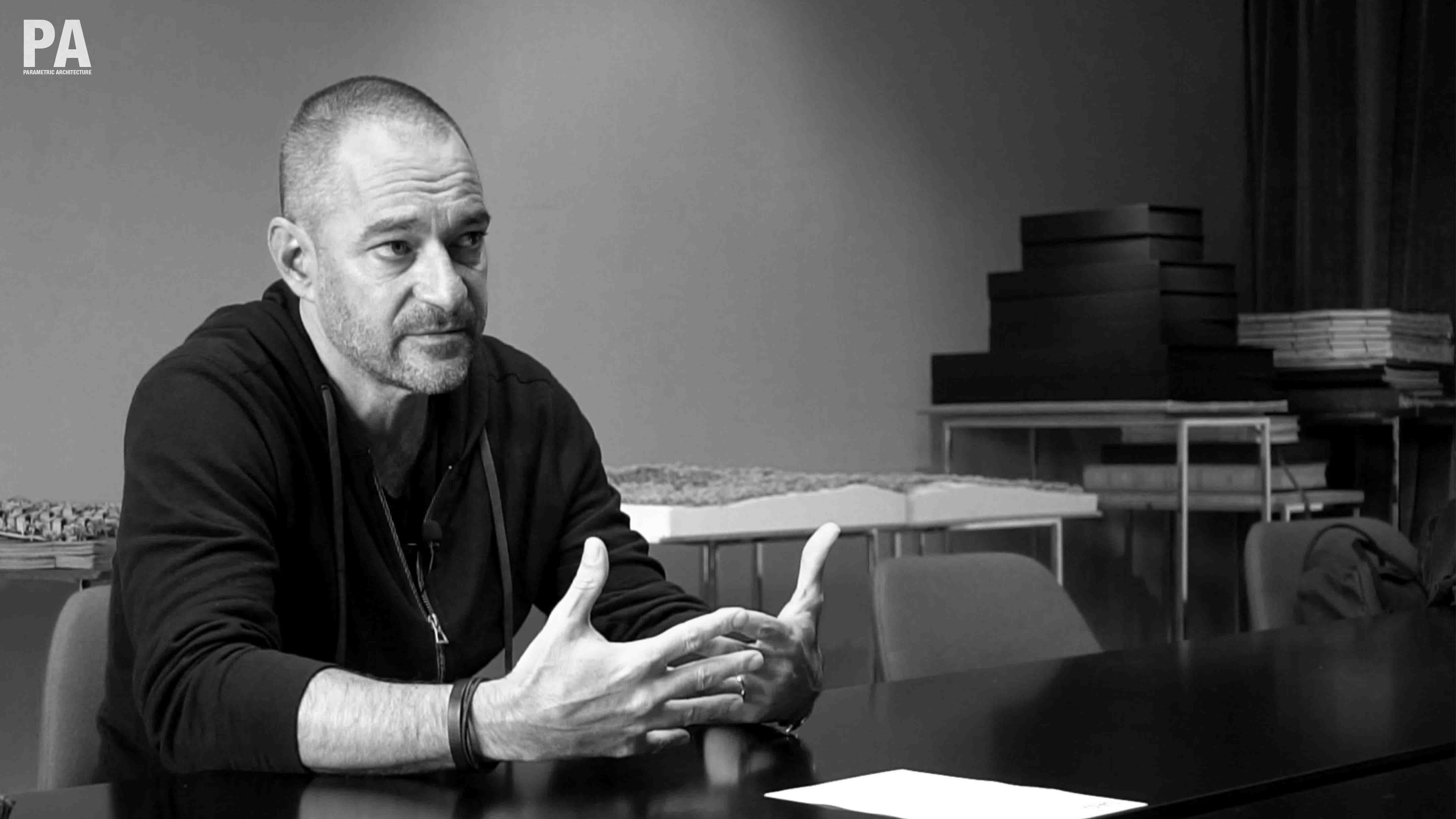

This article is the written format of our interview with Ferda Kolatan as PA Talks 003 which has been released recently. This interview is sponsored by GAD Foundation.

Hamid Hassanzadeh: Dear Ferda, Thanks for being at the GAD Foundation for an interview. This interview is sponsored and organized by GAD Foundation and Parametric Architecture magazine. We invited you here to ask a couple of questions about your academic and work experience in architecture, you are an associate professor of practice at the University of Pennsylvania, and you have lectured on many leading architecture schools around the world. Also, you have your own architecture practice which is called SU11.

So our first two questions are from Gokhan Avcioglu the founder of GAD Architecture and GAD Foundation.

Gokhan Avcioglu: Last week you brought your students to Istanbul from your studio at PennDesign to work on a studio project. Would you please tell us what was the results of visiting Istanbul?

Ferda Kolatan: First of all thank you very much for the invitation. The studio we took from the University of Pennsylvania is the final year of the graduate program at the school of architecture. We took thirteen students to Istanbul just last week and they have already returned and the focus was the area which is called Tophane and it is adjacent to a large development that is ongoing as we speak which is the Galata Port. And the Galata Port has been a very important site politically as well as in terms of its history and its meaning to contemporary Istanbul. it used to be the terminal for large cruise liners. And it has been renovated as we speak. The Istanbul modern which is the modern museum of Istanbul used to be located on the site and it has been taken down and a new building will be built. They will move back. So it’s a very important site and that site is being developed as I said as we speak.

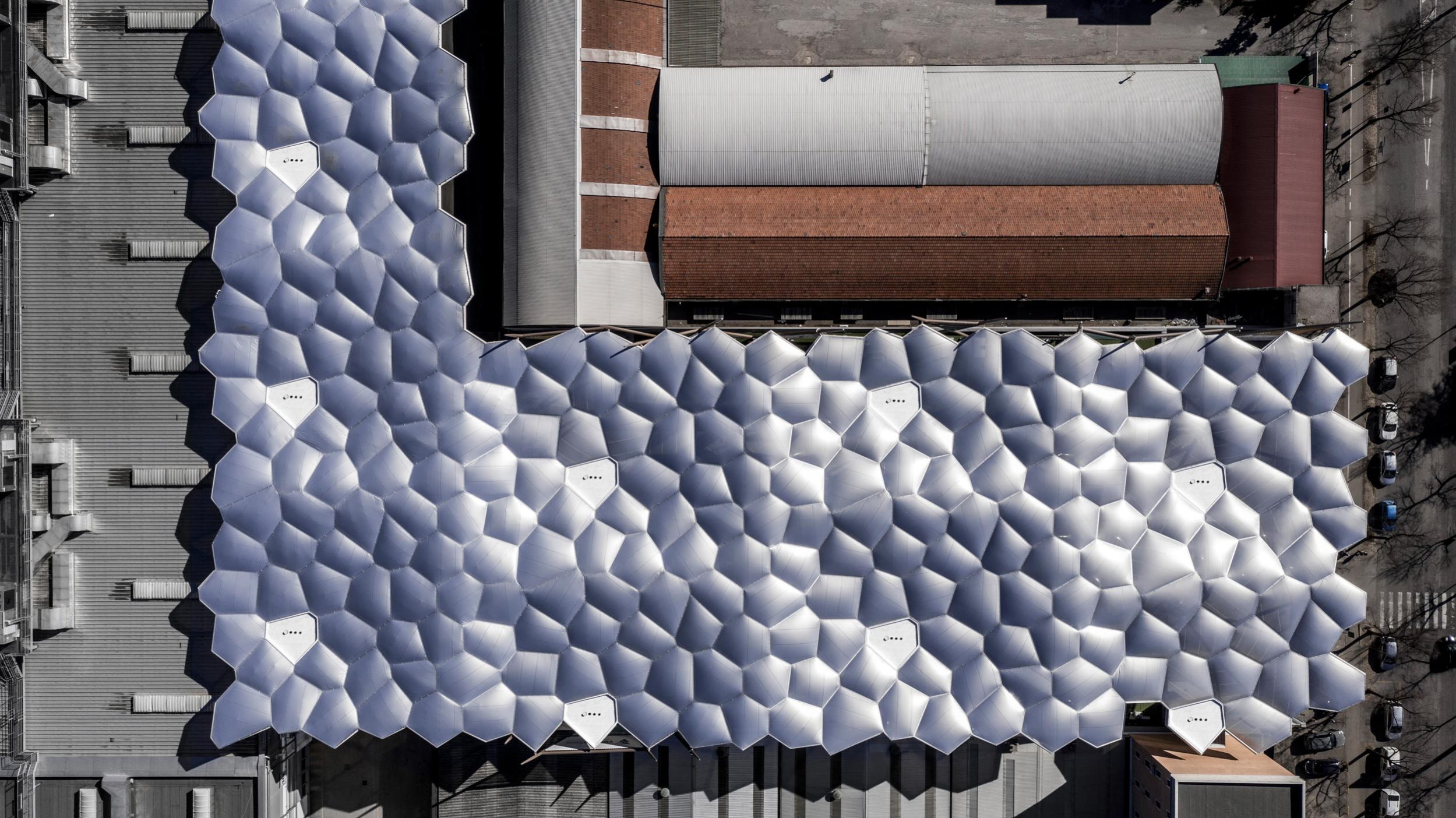

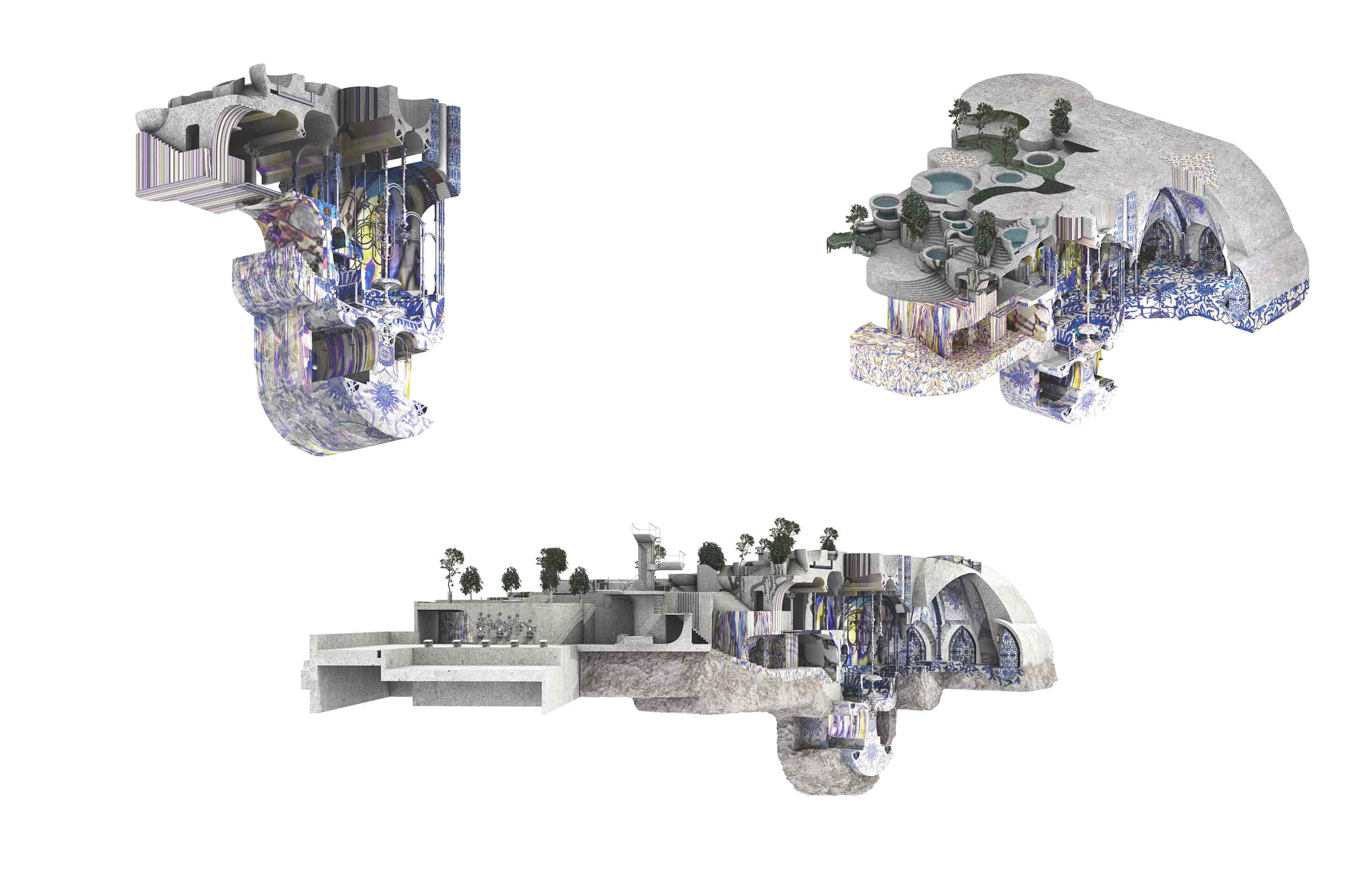

Photo by: Kolatan Studio – PennDesign

Our interest was not to look directly on that site but understand how that new site is going to be connecting back to the city. The Galata Port site is flanked by three different neighborhoods and we focused on particular two of those: Karakoy on the one side and then Cihangir behind going up the hills. And We realized that over the history of urban development the Galata Port area has been cut off by a road and also by this deep incline of the hill that is right behind that road. So our focus is to develop an architectural, cultural, and infrastructural solution that acts as some kind of in-between space, between the newly developed port as well as the existing neighborhoods. the neighborhoods are very diverse so there needs to be a diverse response to the way how we look at that site. So our goal is to make connections but also articulate separations as well. we are not interested only in making bridges, connections everywhere but, we want to understand at some point where hard breaks could also be useful for the city. So also it’s a supercharged and very interesting site, historically in terms of infrastructure, but it will also become a very important contemporary beacon of modern-day turkey once it’s completed. So that’s why we choose that site.

Gokhan Avcioglu: You have recently started your Instagram account and you are uploading your students work on your feed. We are really wondering what would be the results of their works. How do you see the project will go?

Ferda Kolatan: There is a certain kind of methodology (or better not to call it methodology because it is not as clearly prescriptive) but there is a design approach that I have been developing over the last maybe three or four years. Projects that we did in Cairo have a similar signature. The idea is to think about contemporary design, not through means of abstraction which is a kind of common modernist topic that we abstract legibility to a degree that it becomes Universal and that has been, I would argue for the last hundred years a very strong impetus, how quote-unquote contemporary and modern design was thought about. I am really interested in avoiding abstraction and coming to a novel design expression a contemporary by actually being very literal with historical material, infrastructural material, geographical and organic material like park, trees and etc. and hybridized them in ways to generate these conditions, objects, and scenarios which we would call hybrid because they truly begin to form a relationship or respond to each other in unexpected ways.

Photo by: Kolatan Studio – PennDesign

This particular studio has another name even, it is called Oddkin which I borrowed that term and it is basically the idea that what we bring together doesn’t even have to be harmonious, but its relationship that is at odds with each other, but that tension is something where an opportunity for architecture arises.

My Instagram is basically the students studying found objects quote-unquote “architectural objects” as well as infrastructural objects on the site looking very carefully toward pattern, color, and texture and bringing them into contact with each other in new ways. This is our main approach and let’s see how we will be able to build it up to a larger urban scheme. So the challenge with this type of work is it is one thing to design a building or smaller object with this idea and it’s a whole other to bring it onto the scale of urban design. And that will be my challenge I am really excited about. By the way Donna Haraway is the philosopher that coined the term Oddkin and I borrowed that notion from her and I think it is a brilliant word to use operational term.

Photo by: Kolatan Studio – PennDesign

Hamid Hassanzadeh: How architecture education is organized in universities like UPENN to change and adapt with the upcoming design tools and technologies?

Ferda Kolatan: UPenn has for many many years been taken on a leadership role in a way how they deal with technology how we deal with technology. I would say the development of the use of technology at an institution like Penn’s architecture school has been echoing an overall trajectory of how the leading American schools have been dealing with technology. At least those schools that have a particular interest in design and what I mean but this is the type of design that is material, formal, structural, textural. The innovation comes through novelty in those material categories and how can the technology that we use help us to express new kind of material conditions. In the early days it was very strongly based on understanding what the technology can actually do because of the technology itself, the digital technology that we are talking about were new. They needed to be tested, they needed to be understood. And often projects looked like the results of playing around with technology to really understand what they would create.

Kolatan Studio – PennDesign

I myself taught digital fabrication courses since 2006 at UPenn and I know at the beginning just a production of a tool was interesting because we saw things that we had not seen before. The second phase then became about what can we now do with the things that we produce, and how we can channel them towards architectural questions and problems. And then I would say in the last few years including today, technology has matured to the level that it sinks back into the background. But it is no longer at least a way at UPenn overtly the aesthetic that the projects produce. It is more intricate other kinds of motivational design qualities feed into it and another type of hybridization is happening between technology and other tools of design as well as an understanding of history and side and place and that kind of conglomeration or melange is producing I would say a lot of the work that you see at UPenn. So there has been that sort of evolutionary trajectory of a kind of orthodoxy of the digital is being softened up and now generating more layered and varied results.

Hamid Hassanzadeh: There is always a gap between architecture programs in universities and the real practice which put students in very hard situations in the first years of their work experience. Regarding this issue what would be your strategies to train the students for easier adaptation?

Ferda Kolatan: That is an interesting question. It is actually one we discussed quite a bit in the United States as well. There are usually two different ways of looking at this. The way you posed the question it comes from one particular point of view which is to say that the university or education’s main purpose is to prepare the students to have an easy transition to the world of practice. There is a counter position to that which is to say that higher education in architecture in particular postgraduate and post-professional is supposed to do the opposite. It is actually supposed to alert the student to the challenges and the problems of the world which sometimes includes the practice of architecture. So I don’t want to make it sound too much like it is a confrontational balance between the academy and the practice world but I’m certaily more on the side of those who like to forge a criticality in the students so when they go out into the world, they are not too easily absorbed into the existing. But they bring with them an ability to be critical and therefore to engender change. So the agency of change that comes through the way we educate them on the highest level.

Now I have said that of course nobody is served by creating a divide like a wall between the academic world and practice world because then they would not cross over the practice world will do whatever they do. But I think it is a fine line and we should not just try to produce the perfect employee or ever the perfect architectural principal to operate in the practice world because a lot of the things that happen in the practice world which we all are very much aware of it they are far from idea and they need change. So for us to be able to engender that change we need to educate students in a way that they ask those kinds of questions. I see my main role as an educator to instill that type of critical thought in the students.

There is no solid block of architecture program and every one of them are very different. First of all, I think we need that difference. I don’t think you can have an individual universal idea of how architecture education should happen. I am very aware and familiar with architecture education in the United States and in some countries in Europe like Germany and even Turkey, they are very very different for obvious reasons. So it’s important to me to understand why a school and particular context, particular country educates their students in a particular way. Now if you ask me as a professor at PennDesign, I would come back to the question and say yes I want my students to challenge the status quo rather than prepare them to fit right in.

Hamid Hassanzadeh: What is the role of the history of architecture in today’s digital world? How it is feeding the context of computer-based designs?

Ferda Kolatan: I will speak to how I look at it because for everybody this is a very specific question. So I am not making a larger claim but other people do. There is a lot of history that we see in this day and age coming back very clearly into design expressions. So different people may have different ideas about why they did it and why they do it. I’m interested in history mostly because of what I said early on trying to avoid abstraction.

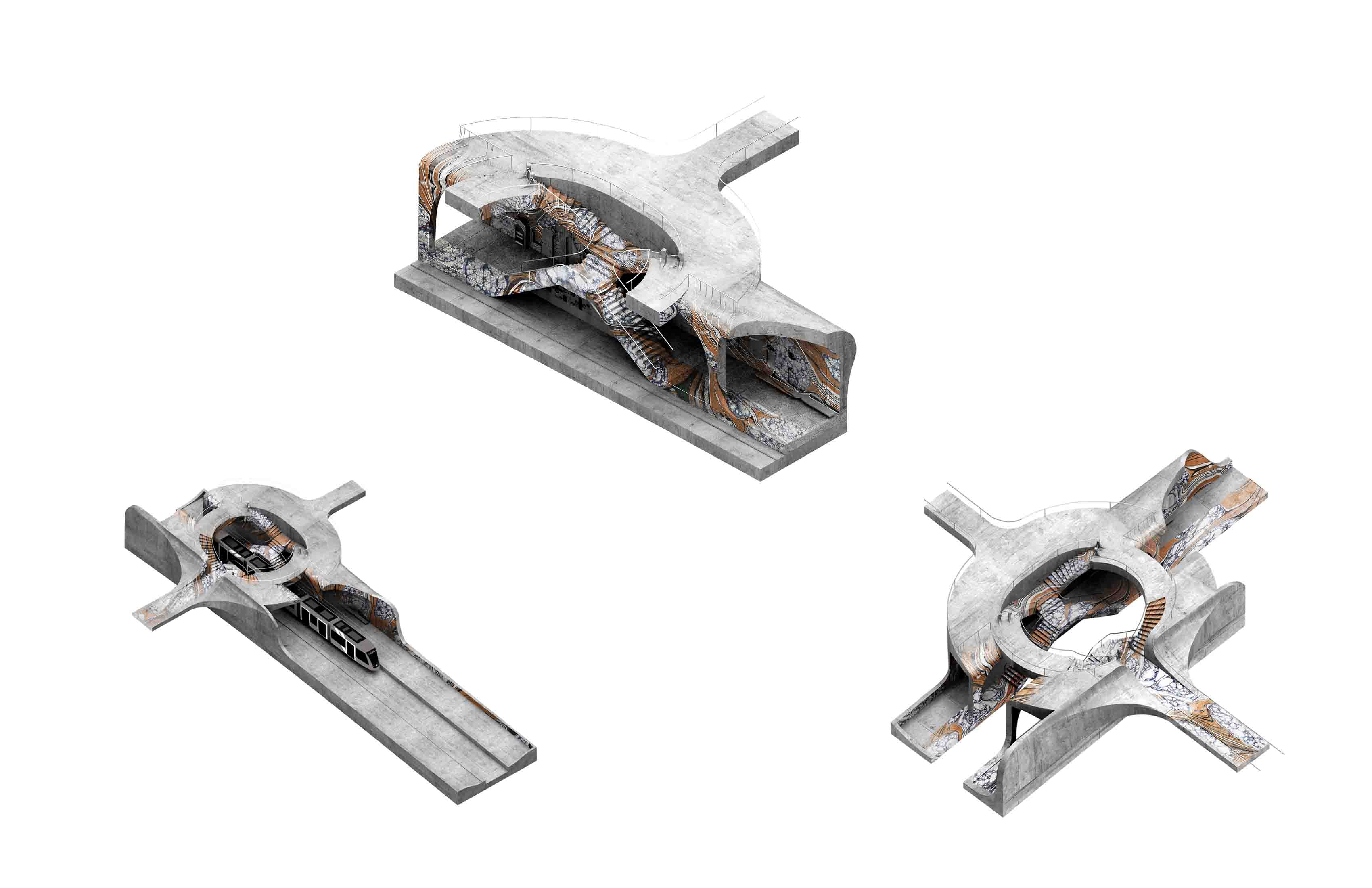

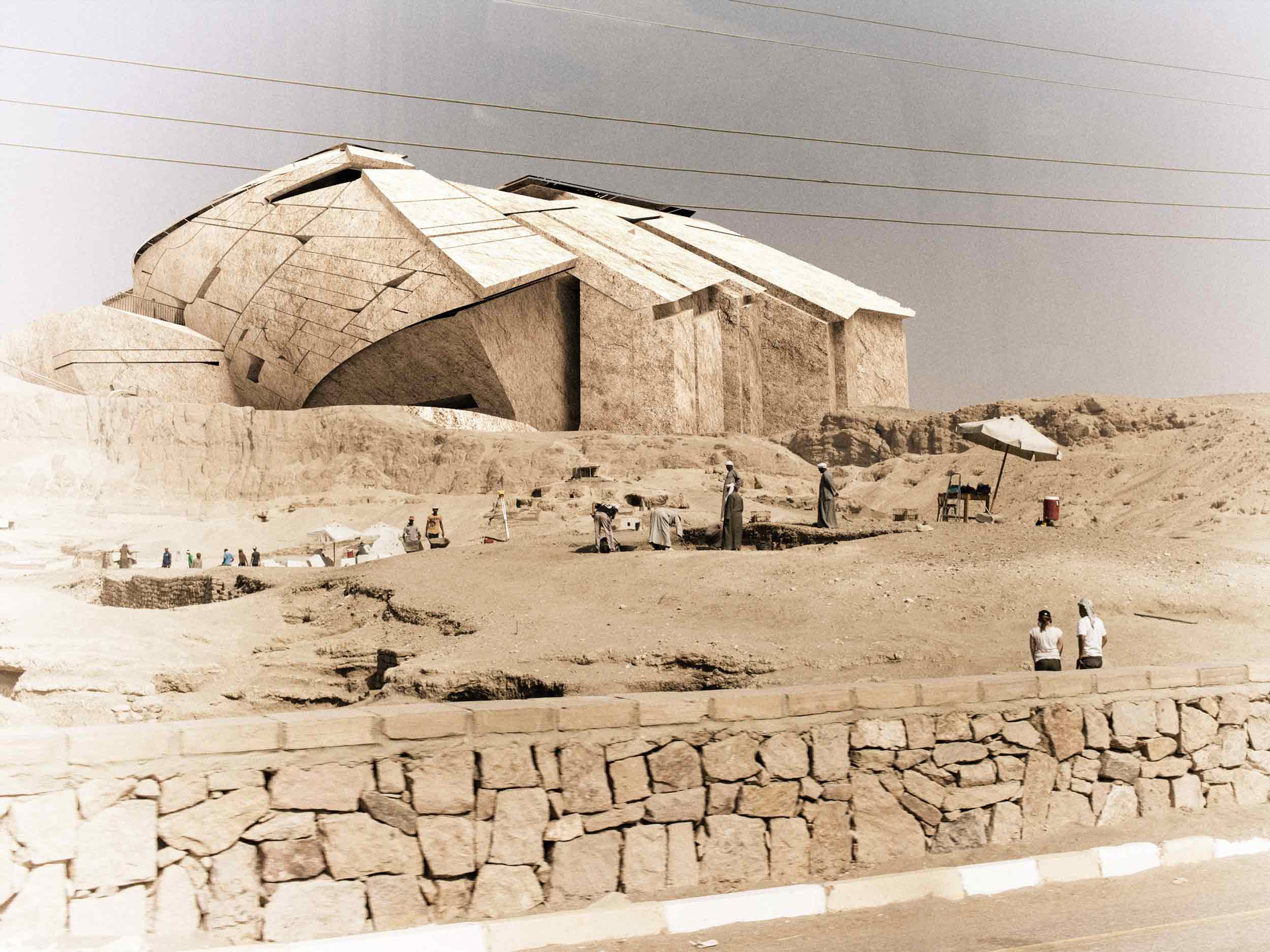

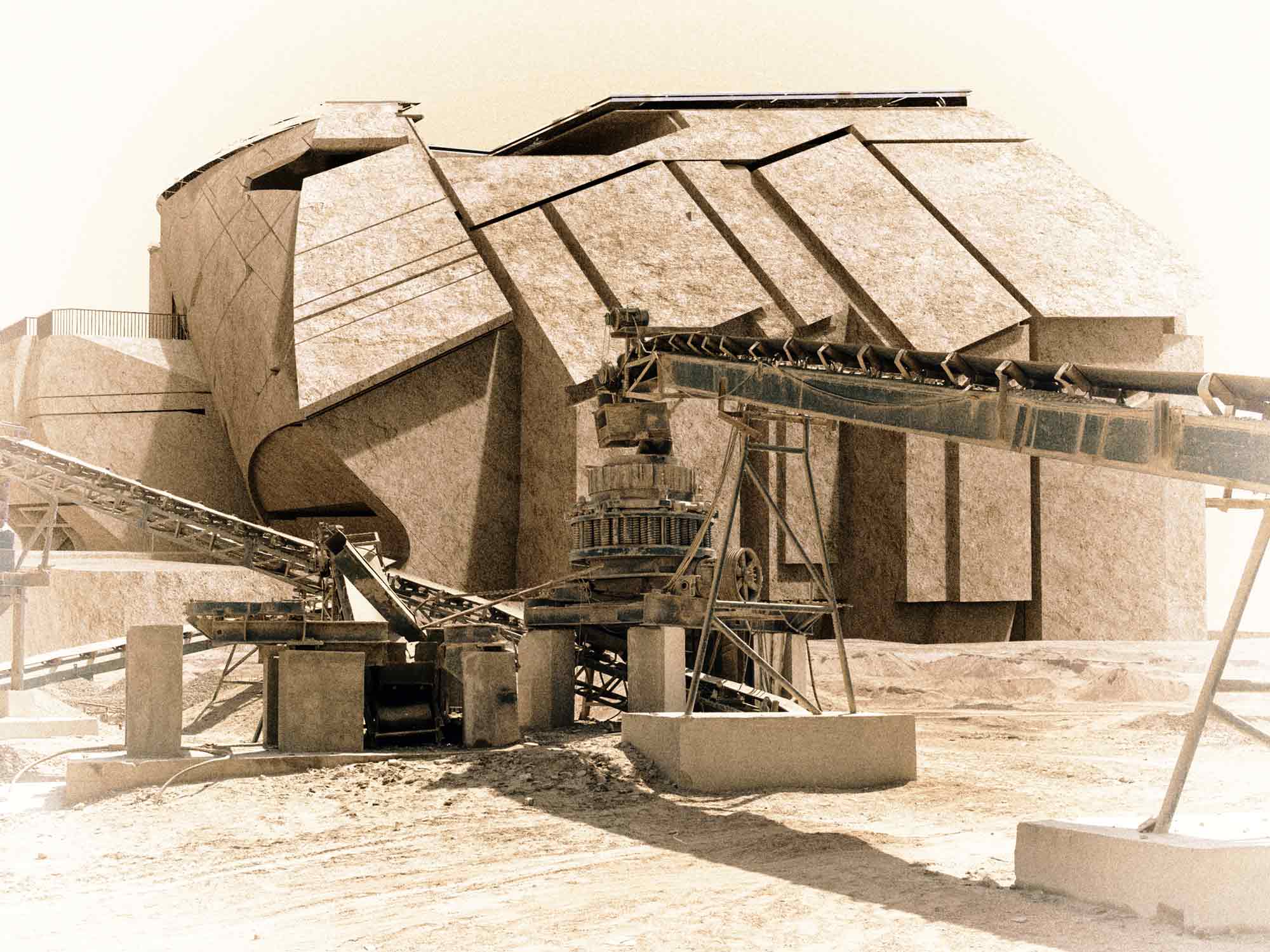

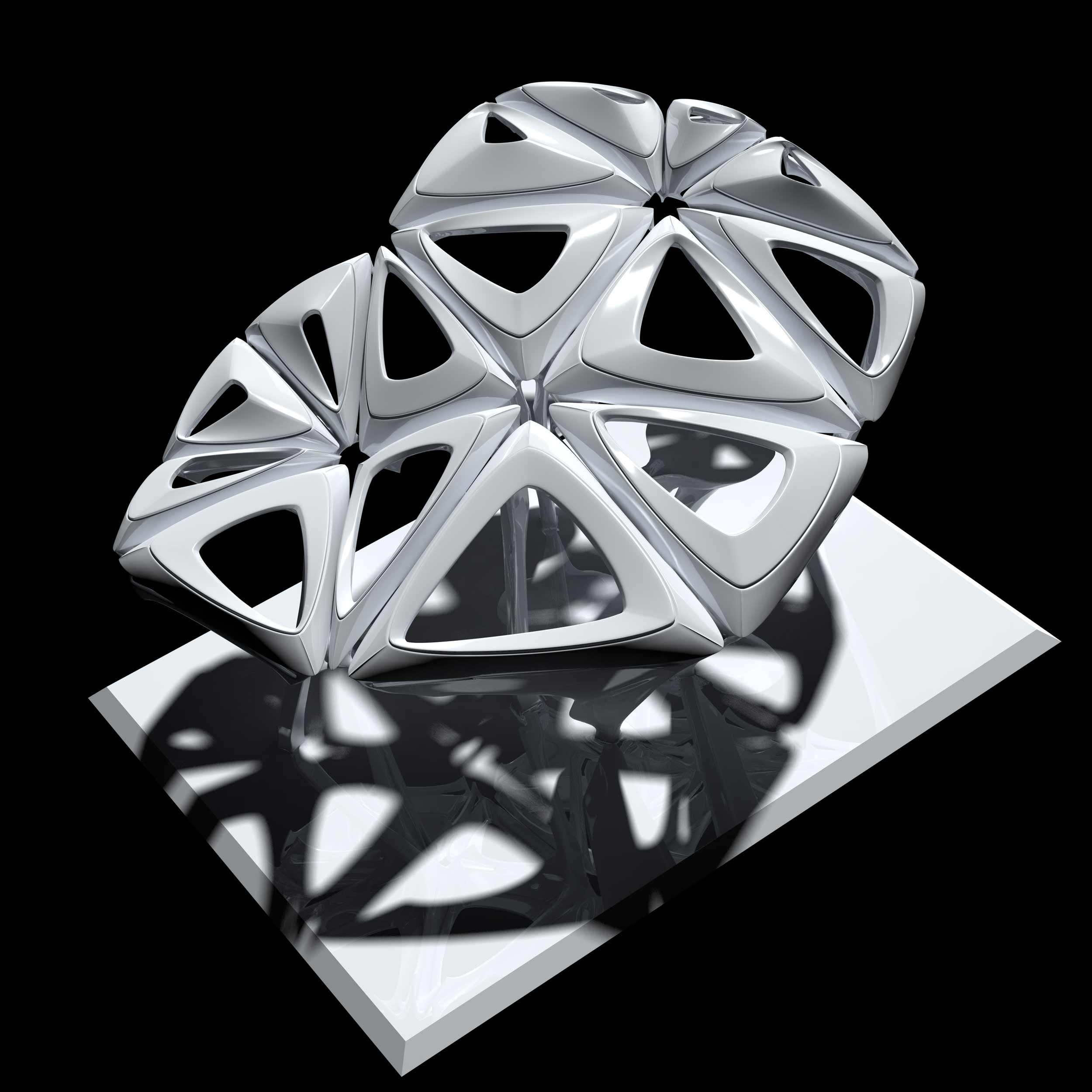

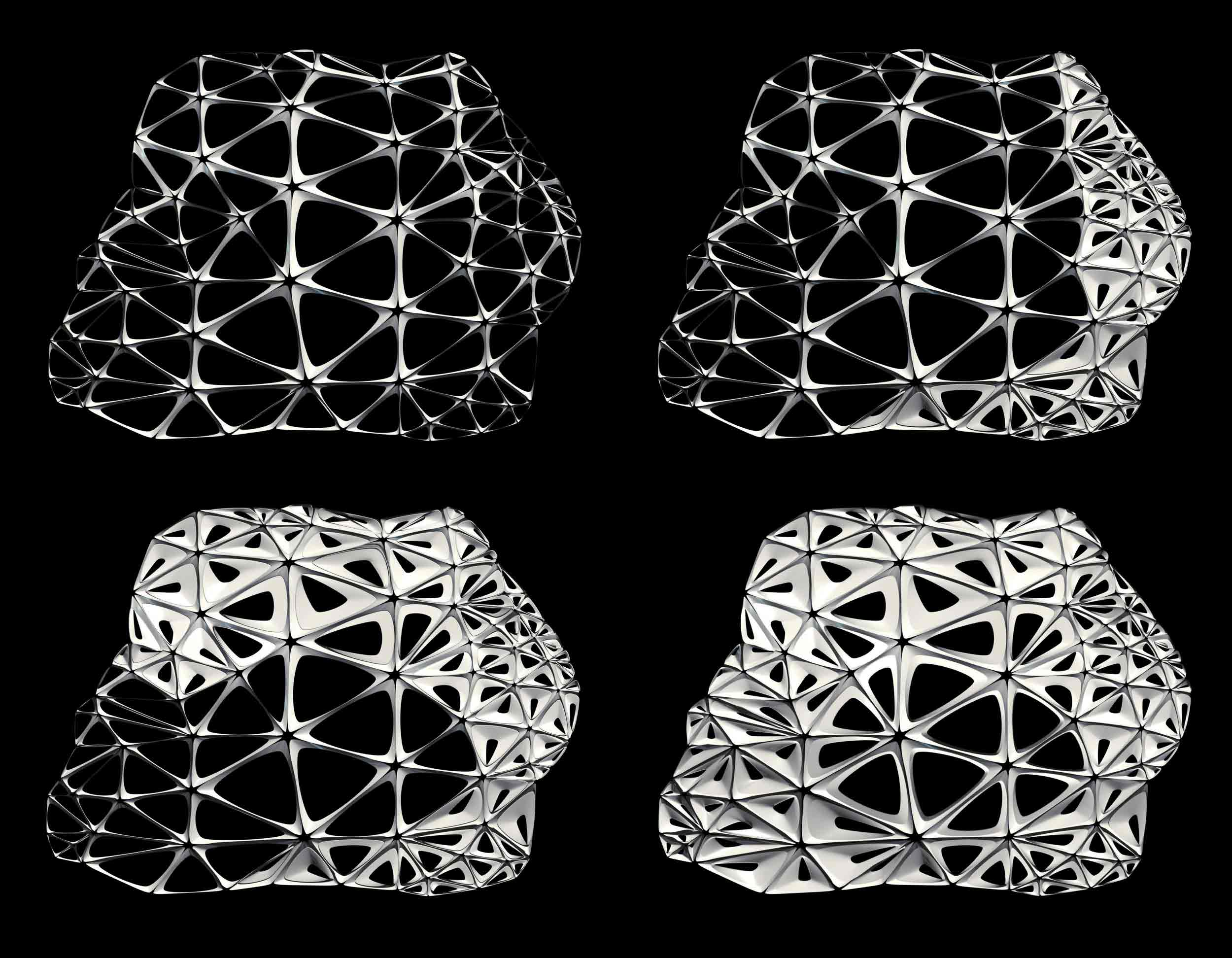

Science City – Cairo, Egypt – SU11 Architecture+Design

If I work on a project and there is a context of that project which usually unless you are building somewhere on Mars you do have some kind of build context you have to deal with it in some way or another. I’m not a contextual as my interest is not to say I want to design buildings that fit in. I’m coming from the point of view whereas there is a lot of strange idiosyncrasies everywhere and I’m interested in those the things that challenge and easy consumption of architecture. I like things to be difficult and not easy because I believe when they are difficult they will force you to spend more time with the thing at hand try to understand it on a deeper level. It is not easy to move on and say OK this is what it is.

Science City – Cairo, Egypt – SU11 Architecture+Design

So history to me is one of those components. And history is very complex. If there is historical legibility and some of the designs, it is utilized to express complexity and difficulty. It is by no means meant to just sort of refer to history as the thing that we need to uphold. I take a lot of liberties what I do with historical architecture in the context of the projects that we work in. I kind of use them literally like tools (conceptual tools) as well as design tools. It matters a lot to me. I love history but it is not a historical I would never want the design that we produce to be misunderstood as some kind of referential architecture or historic architecture.

Science City – Cairo, Egypt – SU11 Architecture+Design

Hamid Hassanzadeh: When we search about your works we see that you are designing on a variety of scales, we see a massive science center in Cairo, interior designs, then the scale goes even smaller like column design, and etc. What is the benefit of working on different scales? How it affects design capabilities?

Ferda Kolatan: This is a very interesting and kind of a personal question or the answer will be personal. Before anything, I probably see myself as a designer even more than I see myself as an architect. I don’t know when that happened because I know when I was a student I was not thinking that way, but somewhere along the way, I came to the realization that what matters to me really is to just design stuff, to conceptualize and think about them and then design it.

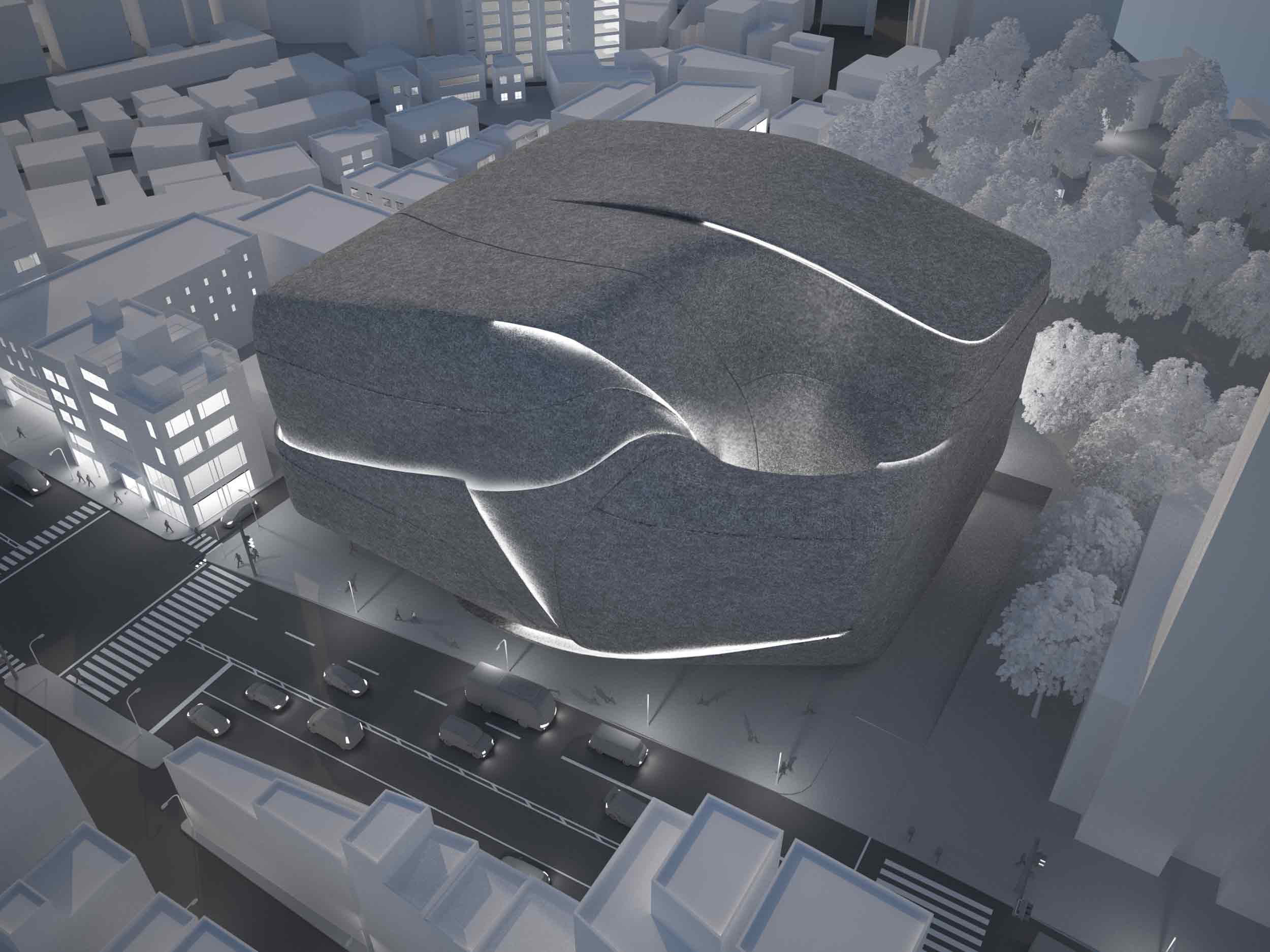

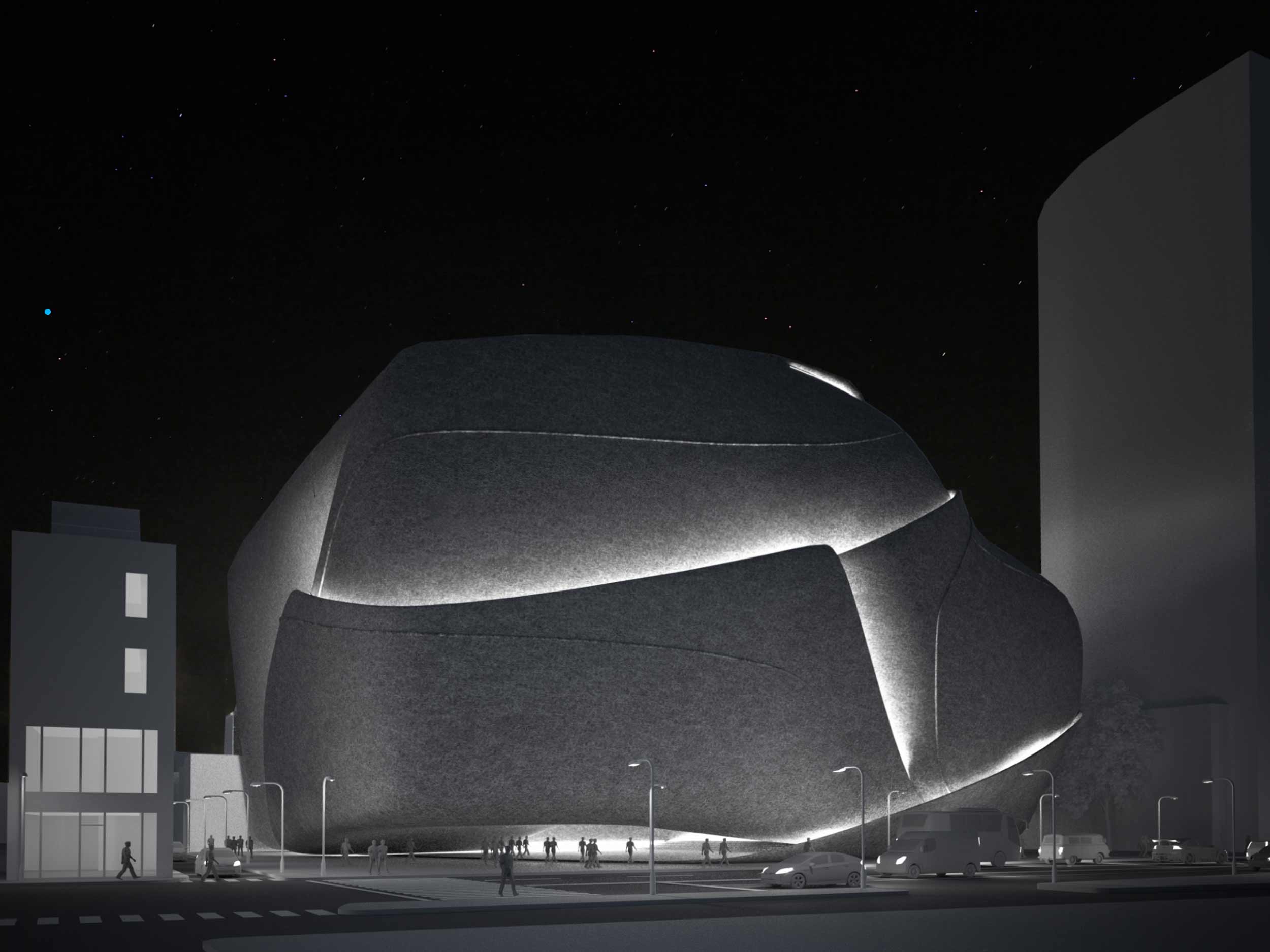

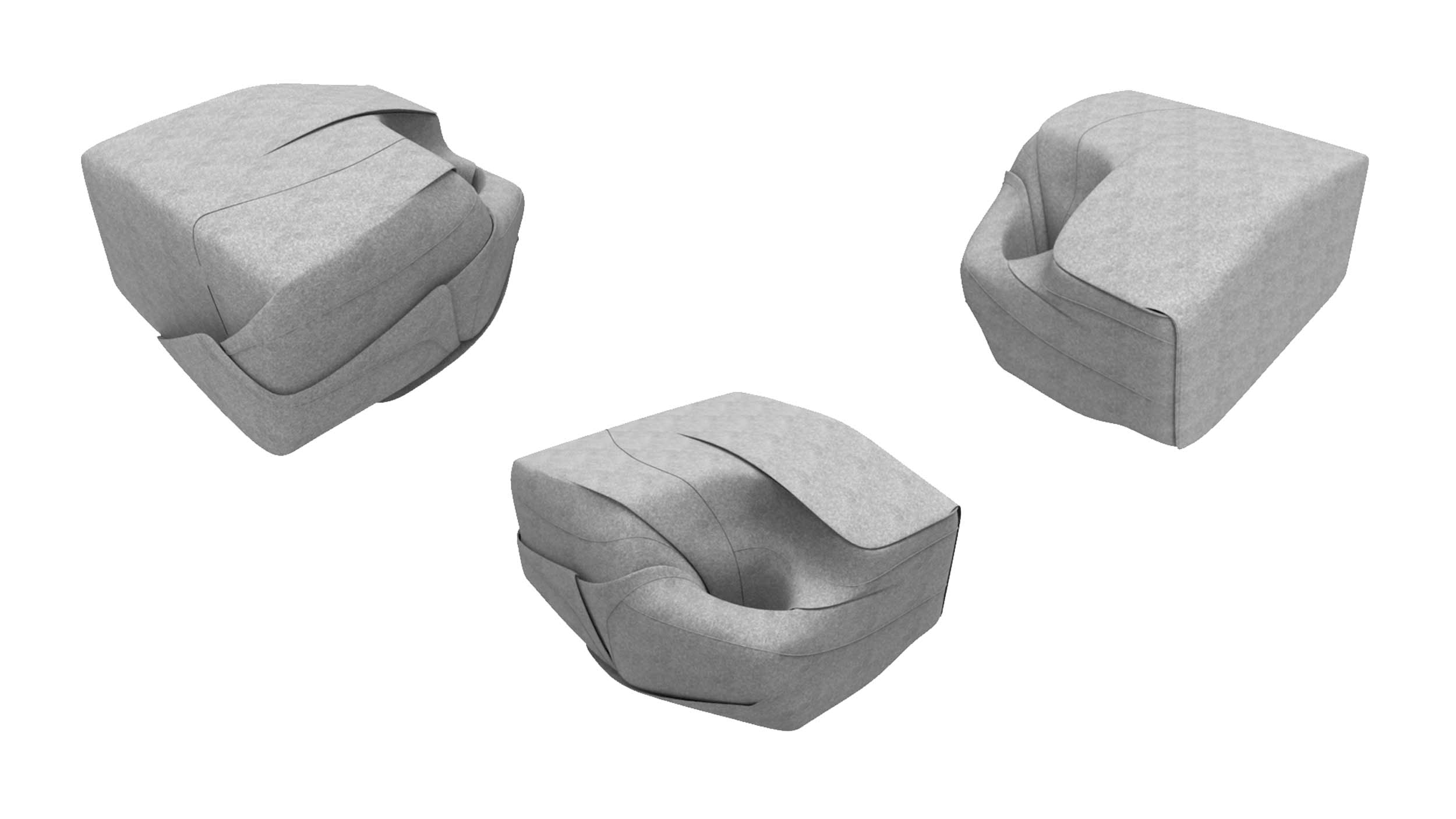

Tokyo PAC – Tokyo, Japan – SU11 Architecture+Design

If it takes the form of an object, an art piece, an installation, an interior, exterior building, small or large city. To me, it is literally just the change in scale but each one of these challenges is equally interesting and important to me. There is a lateral connection to these kinds of problems. Now clearly the small scale object cannot be translated too easily into a large-scale architecture.

Tokyo PAC – Tokyo, Japan – SU11 Architecture+Design

You have to think and rethink what it is you are doing according to the scale but there are certain ideas and principles that can travel or have echoes. We often do something small and then we find an element within that small which we then translate into a much larger project. And the larger project is very different and has to act differently functionally, programmatically, aesthetically and yet there are these moments that echo another project that we had generated earlier. So that’s the main reason I would say.

Tokyo PAC – Tokyo, Japan – SU11 Architecture+Design

Secondary also it is a little bit like an exercise. For example, exercising for a piano piece you need to do certain finger exercises. So you don’t get to build larger buildings all the time or even work on larger competition kind of buildings. So the kind of finger exercises as I often use art type projects or where the result is not something you would traditionally call the building. But I like to look at all of it as design/architecture.

Coral Column – Tokyo, Japan – SU11 Architecture+Design

Hamid Hassanzadeh: You always have mentioned that in design the final product is more important than the process. What are your thoughts for valuing on the final product more than the design process?

Ferda Kolatan: There is a really simple answer to that. I mean at the end of the day you go home you are done and what remains is the final object, final product, final building, final idea, final concept and whatever state that architecture is expressed itself. That’s what we see, that’s what other people see, that’s what’s in the world.

Baltic Thermal Pool Park – Liepaja City, Latvia – SU11 Architecture+Design

I don’t believe in a design where an explanation of the process or even an understanding for those who are not producing is an understanding of those of the project has to be based on the process. I think the process is very important, and I don’t think you can do good design without it. You need to know what it is you are doing. You need to be an expert and you need to do it over and over and study and whatever it is you use in the production of architecture and that process you need to control. The more and the better. But it’s not something that has to become sort of value of the final outcome.

Baltic Thermal Pool Park – Liepaja City, Latvia – SU11 Architecture+Design

Hamid Hassanzadeh: You have also worked on the parametric design. How would you define it? And what are the most important features of this design approach?

Ferda Kolatan: Well, that’s in a way a loaded question. I feel more comfortable to call it digital design and not parametric design. Because parametric design falls into two camps. We either talk about Parametricism which is what Patrick Schumacher is talking about in his books and he very clearly determines what he thinks Parametricism is. And then there is a parametric architecture which is basically a design that has been produced with certain kind of software which we call parametric software. So there is no particular conceptual or ethical idea connected to parametric design. Parametric design truly is a tool and Parametricism as a much larger framework well defined by Patrick.

PS Canopy – New Orleons, LA – SU11 Architecture+Design

So if I can change the question to a little bit to digital overtly sort of digital design, when we started in the 1990s and mid-90s when I was a student and then a young practitioner in the late 90s the digital was just this fantastic new tool that came out of nowhere. And we were simply just fortunate as a generation to be at the right time at the right place if you were at one of the places that engaged in early digital design. I was at Columbia University and Columbia University under Bernard Tschumi back then it was among the first institutions that really strongly push to work with digital tools. We had the famous or infamous first paperless studios where students were asked to design only with a computer, nothing else. I happen to be in one of those studios. There were three and I was in one of those people the studio’s run by Greg Lynn.

PS Canopy – New Orleons, LA – SU11 Architecture+Design

It felt exciting and it was new, we didn’t really know at all what it would yield. It wasn’t just going to the studio having already seen what been produced and then basically reproducing it. It was truly experimental and Greg was great that way because he forced us to use software that was not meant for architecture. We were asked to use animation software which today is a common thing but back then it was was not. We used Soft Image and this was before Maya was even on the market. I think Maya came on the market in 98 and this is fall 94. But it’s similar and it’s a software that doesn’t allow you to just draw lines and extrude them into walls and you have to work with UV and surfaces. And we were really challenged to understand the geometries that would come from this particular tool and then ask ourselves what it could do for the discipline of architecture.

Now to me, there’s a Parametricism in there but the challenge was not to create a more efficient or more functional design. The challenge was how you break down pre-existing idea of what we thought architecture is about with the introduction of a new tool. Often we refer to it as some kind of paradigm shift an I still believe it was a paradigm shift. Where it’s not only a tool but the whole way of thinking about the world was altered by the introduction of a certain kind of software. Again there was, of course, architecture software were being already used for more than ten years in the mid-90s but it was AutoCAD, MiniCAD and basically computational tools that were mimicking how the architecture already draws. We used to draw like this and then we draw like that on the computer. The big difference with the parametric or parametricist or digital approach was that we didn’t mimic how architects work prior but we tried to sort of simulate kind of architecture around, the one that’s again based on tools of animation privileges and UV’s versus XYZ space, moving away from a Cartesian understanding of the world to one of the topologies. These were all major changes that we were thrown into.

PS Canopy – New Orleons, LA – SU11 Architecture+Design

To me it was a wonderful time really we felt like pioneers but like everything else, there is no endless experimentation with one particular tool. It builds up it matures and at some point you as different kinds of questions with the same tool. And then what happened is the experimentation became less and a new kind of language arose which today we can all identify. We know the architects who do that kind of work, we know how those buildings usually look so it has become a different kind of animal if you will. Some of the most recent tendencies to bring in history and as you know we see a lot of postmodern like architecture from the young generation coming back. I think they are all reactions to the trajectory that the digital project has taken over the last twenty or twenty-five years.

PS Canopy – New Orleons, LA – SU11 Architecture+Design

Hamid Hassanzadeh: Would you please tell us what is your inspiration in Architecture?

Ferda Kolatan: Many things. If I’m focusing on architecture itself which is not the only inspiration, I would bring that back to the early part of the interview lately I would say I’m interested in hybridization, misfits, Oddkins, and idiosyncratic expressions of design. I think that’s a more true expression of our contemporary moment if you will. It seems everything goes on many levels not only in architecture but also in art and even in other creative fields. We are not in the time of orthodoxy. We are not in the time of classical modernism where avant-garde is pulling on the string. Maybe we had that in the 90s for some time as I was just mentioning but right now that one string has unfurled into many and many different bits and pieces and we are pulling sort of still collectively, still knowing where they all come together at some point in history not that far not that long ago. But it has become very very diverse and as I would say not only diverse but idiosyncratic. They’re weird and strange and peculiar architectural qualities that we see being expressed by a whole variety of designers.

I look for those and I also like to look for those in existing and old architectural examples. One reason why I love coming to Istanbul is I know that in the 19th century there have been a whole set of Ottoman examples of architecture that mix and blend with baroque, late baroque elements, rococo elements, empire style elements. All these were considered to be impure at some point in time and yet there is fascinating conglomerates of different ideas and different styles and the way how they come together to create these seemingly ambiguous qualities. That’s what I’m the most interested in.

Hamid Hassanzadeh: Thank you for your time, in closing, may I ask what advice would you like to share with young architects?

Ferda Kolatan: The simple questions are always the most difficult ones. Particularly if you don’t want to give any kind of platitude answer for this type of questions but I think we are at a time where a lot of different ideas seem to co-exist simultaneously. It’s basically a lateral way of perceiving the world rather than one that is sort of vertical. I would recommend that any young person and architect or anybody who is interested in the field of design needs to do many things really well at the same time. To me as I was also answered in regards to the design question and scale question, what really matters is how to develop a kind of a longer conceptual idea within which you can build a career.

In the old days, Peter Eisenman causes a project. What is your project, what are you working on? I don’t know if I see it exactly in those terms but I do agree that it’s very important in order not to get lost in this sort of lateral flood of ideas and images that come up and disappear within minutes. It is to find a way of navigation and a way of production. Bringing the world of images that is growing constantly to bear into how we manifest form and physicality. Start as early as you can that would be my advice. Don’t just sort of do things quickly without taking your own time to sort of step back a moment and conceptualize the moves you have done so you can build up on them in some kind of way. This building up doesn’t have to express itself formally as the same thing. I don’t think we can do that anymore. I don’t think an architect can basically have a 50 year with buildings that all look the same. I think that’s over with. In this day and age, it will not survive it will not keep people’s attention and you don’t have the time to develop that kind of project. Things are too quick.

So how do you figure to build sort of consistency in your work in these circumstances is something I don’t have an answer for but it’s something I would ask every architect and architecture student to think about.

Thank you!

Thanks for reading this article. You can also watch the full interview from our YouTube channel or from the link below.